There’s no question: Nursing is a stressful occupation. It’s not just the sheer volume of patients, the frenetic pace, and the operational and fiscal expectations weighing nurses down. The pain, suffering, and death they experience daily cuts deeper. In fact, a study in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine found that 24% of ICU nurses and 14% of general nurses tested positive for symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

But Daniel Doherty, MSN, RN, CEN at Christiana Care Health System, says the trauma nurses experience extends beyond PTSD to a condition he labels vicarious trauma, the end result of the constant compassion fatigue they experience at work. Vicarious trauma changes nurses in often profound ways, and it’s not just the nurses who are impacted; family, friends, and loved ones all experience the results of these changes. It doesn’t help matters that the distress caused by that vicarious trauma often gets stuffed away, manifesting in a protective detachment that may affect personal relationships and overall health and well-being. And, Doherty explains, some of the burden nurses experience is inevitable just because of how humans are hard-wired; unfortunately, we’re biologically predisposed to negativity.

Doherty has been an emergency department nurse for over 20 years and a staff development specialist in the emergency department. He says the human brain immediately catalogs a negative experience whereas a positive experience takes 20 seconds to register in the brain as a memory. That’s because when we’re stressed, adrenaline and cortisol hormones fire up our limbic systems and pre-frontal lobes, causing us to function in reactive mode. For most nurses, reactive mode is a familiar place; it’s where they live nearly every minute on a shift, rarely able to catch a break.

The good news is that there are things nurses can do to outwit their negative brains, boost their happy hormones, relieve stress, and cope better.

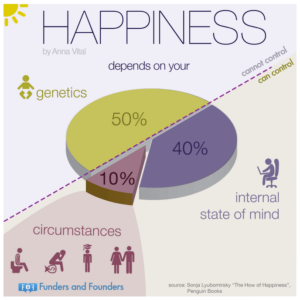

According to the work done by positive psychologist Sonja Lyubomirsky, 50% of our happiness is genetic, 10% comes from circumstances, and 40% is under our control. So, how can nurses make the most of that 40 percent?

Doherty says it’s crucial to recognize that much of the stress in nursing comes from uncertainty and a lack of control. It’s rare that a nurse knows a patient’s story—how it began and where it ends. Their connection is fragmented and there’s really never any closure, and that’s tough on a brain that’s programmed to seek answers. To deal with that, nurses need to remind themselves that their patient’s journey is not their journey and stay mindful about the difference between compassion and empathy. As Doherty explains, the former means we see someone in pain and want to help out, whereas the latter means we see someone in pain, take on some of that person’s pain, and then help out–and that can be a dangerous place for our psychological well-being.

Here are some other coping strategies that Doherty recommends:

- Track and monitor: Tune into all the external trauma exposure you are consciously absorbing and recognize the negative thoughts you’re having instead of disconnecting or “vegging” out, as Doherty says.

- Low-impact debriefing: It’s okay to open up about your stress with those close to you, but you need to give them fair warning before you unleash. You should only share enough information so that you feel better without turning them off.

- Engage with others: Be present in the moment with others. Be mindful of where your thoughts wander off to, try to refocus, and come back to the people front and center.

- Share the serotonin: Some studies show that couples spend only 12 minute per day talking with each other. Make an effort to spend more than 12 minutes speaking and engaging with the people you love and who love you back, and you’ll boost your happy hormones and theirs.

- Follow a symbolic transitional ritual: Do something every day that allows you to transition out of your role as a nurse, whether it’s going for a run, taking a bath, or just changing your shoes. It’s important to switch off your professional life when your shift ends.

- Don’t bring the negativity home: Doherty recounts a story he heard about a nurse sharing her anxiety with her spouse about a doctor at work who hadn’t treated her well. When she told her husband how she hated this doctor, his response was, “Well, if you hate him so much, why do you bring him home?” Keeping the sick, negative, and dead people away from your home will help ensure it’s the sanctuary it should be.

- Do something selfish for yourself: Self-care is vital for nurses. Pouring yourself into others depletes you. Taking care of yourself will recharge you so you can keep tending to others the way you want.

- Plan ahead: Plan something every eight weeks or so. Having something to look forward to—a goal or a vacation, for example—fills your dopamine bank.

- Focus on the positive: When you’re done with your shift, wind down by thinking of three things you did to make someone feel better that day. Give your brain 20 seconds to let the positive thoughts sink in. Focusing on the positive nurtures your dopamine and oxytocin.

How do you separate your work from your personal life? Have any rituals or coping techniques that help elevate your happy hormones? Share what works for you in the comments below or email us your thoughts at hello@nursegrid.com.