For a certain percentage of patients, especially those on Medicare, hospitals have become an undesirable home away from home. They’re admitted, tended to, and discharged, then boomerang back days or weeks later.

Readmissions are stressful for both patients and staff, not to mention costly for facilities. Studies show that improving communication between caregiver and patient has the biggest impact on reducing these return visits. And that puts nurses, the largest segment of our healthcare workers and those most intimately involved with patient care, in a unique position to lower the number of these frequent flyers’ readmissions.

This year, hospitals are projected to incur $528 million in Medicare readmission penalties—a toll that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) assesses based on process-of-care measurements and patient feedback scores found in the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Health Providers and System (HCAHPS) survey.

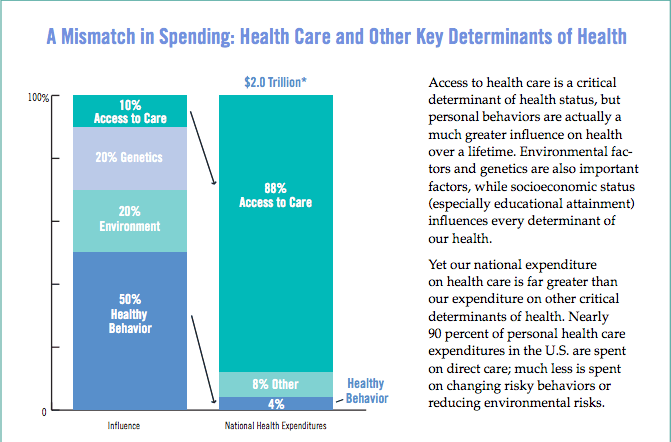

HCAHPS focuses largely on how well doctors and nurses communicate with patients, whether patients are treated with courtesy and respect, the staff’s responsiveness to the call button, how well pain is managed, and other conditions. With so much emphasis on patient communication, it’s ironic that most of the money being invested in improving health care continues to be funneled into medical services rather than promoting healthier patient behaviors.

The hospitals bucking this trend though, focusing more on patient engagement, are finding their readmission rates declining.

The Commonwealth Fund studied four U.S. hospitals with impressively low readmission rates and found that among other strategies, they “try to help patients understand their conditions—and empower them to manage their diet, activities, medications, and care regimens and know when to seek care—through educational activities throughout the stay.” Who better positioned than nurses to ensure patients understand how to care for themselves at home and get the proper follow-up care?

Assuming nurses are appropriately empowered (a big assumption), here are a few things they can do that are proving to reduce readmissions for some facilities:

- Get involved sooner: Ensuring clear communication across a patient’s continuum of care is one of the best ways to improve outcomes, and that means engaging nurses sooner. At Mercy Health in Cincinnati, nurses meet with patients when they are admitted and oversee their care transitions through discharge. By keeping nurses connected to their patients’ care from start to discharge, the hospital realized roughly $495,000 in avoided readmissions in just 10 months.

- Assess high-risk patients at admission: Nurses at California Hospital Medical Center in Los Angeles created a high-risk readmission form to evaluate each patient’s mobility, fall risk, need for oxygen, and other factors. Not only has the facility reduced readmissions, but they’re finding that the “form is engaging staff to become agents of change.”

- Share discharge and self-care instructions early on: When it’s time to leave the hospital, most patients are focused on just that—getting out and getting home (or to their next point of care). For that reason, some hospitals are choosing to impart discharge information at admission or over the course of a patient’s stay. For example, at Boston University Medical Center, “a nurse will discuss a patient’s diagnosis one day, proper diet on another, and review their medications on the third.”

- Follow up: Studies show that 20% of patients have complications or adverse events after they’re discharged from hospitals. Stats like this, along with a CMS ruling that hospitals implement post-discharge follow-up programs, have inspired many facilities to make provisions for nurses to follow up on patients at home via phone calls or home visits. These programs help ensure patients are following self-care instructions and keeping follow-up visits with their primary care providers. At Cullman Regional Medical Center in Alabama, nurses record discharge instructions on iPod Touches, which patients can review from home online or over the phone. As a result, readmission rates have declined by 15%. There are other benefits too. At Stanford Health Care, when nurses started following up with patients over the phone within 72 hours of discharge, patient satisfaction spiked, as did nurse morale.

These are all great ideas, but how can nurses fit in any of these activities along with everything else on their plates today? As we advocated in a recent blog post, the overarching answer requires a culture shift, one that puts more nurses in leadership positions—recognizing their impact on patient outcomes and satisfaction and their influence on controlling costs and shaping system change in general.

In the meantime, giving nurses more breathing room would help too. In a white paper we authored recently, we quoted a compelling statistic: In a typical 300-bed hospital, freeing nurse managers from an outdated scheduling process can open up approximately 6,000 nurse manager hours annually. Those additional hours could be redirected to activities proven to prevent readmissions.

In the same vein, an article in Becker’s Healthcare cites a study showing that effective nurse staffing can help reduce readmissions. Specifically, higher overtime among nurses increased readmissions, while having more nurses on staff working regular shifts (i.e. less overtime) decreased readmissions thanks to “improved discharge teaching quality and discharge readiness”.

Your turn. Do you have any strategies in place to reduce preventable readmissions? We’d love to hear your ideas in the comments below!